Famous Black Americans

African Americans have played a vital role in the

history and culture of their country since its founding. An

important part of the curriculum at the Institute for African

American Studies is devoted to creative research on the lives and

work of prominent African Americans and to placing them within

their cultural context. On this page you will find brief

biographical sketches of several key figures in African American

history.

Benjamin Banneker

1731-1806

Although he spent nearly his entire life on one farm, Banneker

had an important influence on how African Americans were viewed

during the Federalist and Jeffersonian periods of American

history. Born in Baltimore County, Maryland, Banneker was the

child of a free black father. He had little formal education, but

he became literate and read widely. At 21, he built a clock with

every part made of wood--it ran for 40 years. After the death of

his father, he lived on his father's 100-acre farm, largely

secluded from the outside world, with his sisters. Self taught in

the fields of astronomy and surveying, he assisted in the survey

of the Federal Territory of 1791 and calculated ephemerides and

made eclipse projections for Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania,

Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Epheremis,

published during the years 1792-1797. He retired from tobacco

farming to concentrate wholly upon his studies. He corresponded

with Thomas Jefferson and urged Jefferson to work for the

abolition of slavery.

Sojourner Truth Sojourner Truth

1797-1883

Sojourner Truth, a nationally known speaker on human rights for

slaves and women, was born Isabella Baumfree, a slave in Hurley,

New York, and spoke only Dutch during her childhood. Sold and

resold, denied her choice in husband, and treated cruelly by her

masters, Truth ran away in 1826, leaving all but one of her

children behind. After her freedom was bought for $25, she moved

to New York City in 1829 and became a member of the African

Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. In 1853, she helped form a

utopian community called "The Kingdom," at Sing Sing,

New York, which was soon disbanded following the death and

possible murder of its leader. Truth was implicated in the scandal

but courageously fought the falsehoods aimed at her.

After the death of her son, she took the name Sojourner Truth

to signify her new role as traveler telling the truth about

slavery. She set out on June 1, 1843, walking for miles in a

northeasterly direction with 25 cents in her pocket, and rested

only when she found lodging offered by either rich or poor. First

she attended religious meetings, then began to hold meetings

herself that would bring audience members to tears. As she logged

mile after mile, her fame grew and her reputation preceded her.

Truth's popularity was enhanced by her biography written by the

abolitionist Olive Gilbert, with a preface written by William

Lloyd Garrison. In 1864, she was invited to the White House, where

President Abraham Lincoln personally received her. Later she

served as a counselor for the National Freedman's Relief

Association, retiring in 1875 to Battle Creek, Michigan.

Harriet Jacobs

1813-1897

Known primarily for her narrative Incidents in the Life of a

Slave Girl: Written by Herself, Harriet Jacobs was a reformer,

Civil War and Reconstruction relief worker, and antislavery

activist. In Incidents, Jacobs describes her life as

Southern slave, her abuse by her master and involvement with

another white man to escape the first, and the children born of

that liaison. Also described is her 1835 runaway, her seven years

in hiding in a tiny crawlspace in her grandmother's home, and her

subsequent escape north to reunion with her children and freedom.

During the war, Jacobs began a career working among black

refugees. In 1863 she and her daughter moved to Alexandria, where

they supplied emergency relief, organized primary medical care,

and established the Jacobs Free School--black led and black

taught--for the refugees. After the war they sailed to England and

successfully raised money for a home for Savannah's black orphans

and aged. Moving to Washington, D.C., she continued to work among

the destitute freed people and her daughter worked in the newly

established "colored schools" and, later, at Howard

University. In 1896, Harriet Jacobs was present at the organizing

meetings of the National Association of Colored Women.

Alexander Crummell Alexander Crummell

1819-1898

Alexander Crummell, clergyman and author, was born in New York

City to free parents. Crummell was a descendant of West African

royalty since his paternal grandfather was a tribal king. He

attended Mulberry Street School in New York, and in 1831 he was

enrolled briefly in a new high school in Canaan, New Hampshire,

before it was destroyed by neighborhood residents. In 1836

Crummell attended Oneida Institute manual labor school. He was

received as a candidate for Holy Orders in 1839 and applied for

admission to the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal

Church, but was not admitted because of his color. He was

eventually received in the diocese of Massachusetts and ordained

to the diaconate there. After study at Queen's College, Cambridge,

England, he went to Africa as a missionary, becoming a professor

of mental and moral science in Liberia. While there, Crummell

became widely known as a public figure; in 1862 he published a

volume of his addresses, most of which had been delivered in

Africa. After spending 20 years on that continent, Crummell

returned to the United States and became rector of St. Luke's

Church, Washington, D.C., and later founded the American Negro

Academy.

Harriet Tubman

1821-1913

Heralded as the "Moses" of her people, Underground

Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman became a legend during her

lifetime, leading approximately 300 slaves to freedom during a

decade of freedom work. Denied any real childhood or formal

education, Tubman labored in physically demanding jobs as a

woodcutter, a field hand, and in lifting and loading barrels of

flour. Although she had heard of kind masters, she never

experienced one, and she vowed from an early age that she would

strive to emancipate her people. In 1844, at age 24, she married

John Tubman, a freeman, and in the summer of 1849 she decided to

make her escape from slavery. At the last minute, her husband

refused to leave with her, so she set out by herself with only the

North Star to serve as her guide, making her way to freedom in

Pennsylvania. A year later, she returned to Baltimore to rescue

her sister, then began guiding others to freedom. Travel became

more dangerous with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, but she

was not deterred, despite rewards offered by slaveowners for her

capture totaling $40,000.

Tubman's heroism was further highlighted by her activities

between 1862 and 1865, when she was sent to the South to serve as

a spy and a scout for the Union Army. Her gift for directions and

knowledge of geography remained an asset as she explored the

countryside in search of Confederate fortifications. Although she

receive official commendation from Union officers, she was never

paid for the services she rendered the government.

After the war she returned to Auburn, New York, working to

establish a home for indigent aged blacks, and in 1869 she married

her second husband, a Union soldier. She became involved in a

number of causes, including the women's suffrage movement. Her

death brought obituaries that demonstrated her fame throughout the

United States and in Europe. She was buried with military rites,

with Booker T. Washington serving as funeral speaker.

Booker

T. Washington Booker

T. Washington

1856-1915

Born into slavery, Booker T. Washington was the most prominent

spokesperson for African Americans after the death of Frederick

Douglass. Much more conciliatory than Douglass, Washington

sought--but never demanded--social betterment for African

Americans through economic progress. As a boy, he picked

Washington as his last name. After emancipation his mother and

stepfather moved to West Virginia, where Washington worked in the

coal mines but attended school whenever possible. In 1871,

Washington returned to Virginia and enrolled in the Hampton

Institute. After graduation in 1875, he first taught in West

Virginia and then studied at the Wayland Seminary before returning

to teach at Hampton. In 1881 he left Hampton to begin the single

most important undertaking of his life: founding the Tuskegee

Normal School in Alabama. Washington, his small staff, and their

students worked as carpenters to build Tuskegee. In its first year

of operation Tuskegee had 37 students and a faculty of three; when

Washington died in 1915, Tuskegee had 1,500 students, a faculty of

180, and an endowment of $2,000,000.

African Americans have criticized Washington for what they saw

as his overly-deferential attitude to his white benefactors and

for his position that university education was basically

irrelevant for blacks, who should concentrate on vocational

training. This, along with his acceptance of segregation,

increasingly led W.E.B. Du Bois and other leaders to speak out

against Washington. In October 1915 Washington collapsed while

delivering a speech in New York City and was hospitalized. He

asked to be returned home to die and was taken back to Tuskegee,

where he died the next day at home on his beloved campus.

George Washington Carver

1860-1943

One of the best known agricultural scientists of his

generation, Carver was born into slavery near Diamond Grove,

Missouri. Slave raiders kidnapped Carver and his mother when he

was a six-week old infant, but his owner allegedly ransomed back

the boy with a $300 prize race horse. Although Carver had to work

and live on his own while still a boy, he managed to finish high

school and became the first African American student to enroll at

Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa. He then put himself through

the Iowa Agricultural College by working as a janitor, earning a

B.S. in 1894 and an M.S. in 1896 in agricultural science. The same

year, Carver joined Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee

Institute, directing Tuskegee's agricultural research department

continuously until his death in 1943. At Tuskegee, Carver

concentrated on persuading Southern farmers to end their virtually

exclusive reliance on the cotton farming that had leached the soil

of nutrients, producing increasingly poor crops. Carver encouraged

farmers to diversify and plant sweet potatoes and peas. In order

to make these crops more profitable, Carver did extensive

research, producing more than 300 derivative products from the

peanut and 118 from the sweet potato. In 1923 Carver won the

Spingarn award, the highest annual prize given by the National

Association for Colored People. In 1938 he took $30,000--virtually

his entire life's savings--and founded the George Washington

Carver Foundation to continue his work after his death. When he

died in 1943 the rest of his estate went to the foundation. He was

buried beside his great friend and mentor, Booker T. Washington,

on the Tuskegee campus.

Ida Wells-Barnett Ida Wells-Barnett

1862-1931

Born to a slave cook and a slave carpenter, Ida Wells was a

prominent antilynching leader, suffragist, journalist, and

speaker. At age 16 she took over the raising of her siblings after

the death of her parents to smallpox. With the help of the black

community, Wells attended Rust College, afterward finding

employment as a teacher.

In May 1884 Wells sued and won a case against a railroad for

forcefully removing her from a segregated ladies' coach. The

incident served as a catalyst to a more militant Wells. As part

owner and editor of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight,

she spent much of her time writing about the poor conditions for

black children in local schools. After the 1892 lynching of three

of her friends, she was diligent in her antilynching crusade,

writing Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. In

1893 Wells carried her fight for equality to the Chicago World's

Fair, then remained in Chicago and helped spawn the growth of

numerous black female and reform organizations. Wells marched in

the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., and was one of two

African American women to sign the call for the formation of the

NAACP. She married Ferdinand Barnett, owner of the Chicago

Conservator, in 1895, and continued her "crusade for

justice" until her death in 1931. View

the text of Well's 1902 letter to the members of the

Anti-Lynching Bureau.

W.E.B.

Du Bois W.E.B.

Du Bois

1868-1963

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, W.E.B. Du Bois became

the most respected and effective spokesperson for the full rights

of African Americans in the decades before World War II. In 1888

Du Bois earned an A.B. at Fiske University, where he had his first

experience of overt racial prejudice. Returning to Massachusetts,

he earned his M.A. at Harvard and then spent two years studying at

the University of Berlin before becoming the first African

American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard. Du Bois taught at

Wilberforce University, the University of Pennsylvania, and

Atlanta University. Throughout his life Du Bois combined an

illustrious academic career with his work for full rights for

African Americans. He is perhaps best known for his work in

founding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People in 1909 and helping it to become the country's single most

influential organization for African Americans.

Du Bois argued for the creation of a black elite which would

win social equality for African Americans by winning the respect

of powerful educated whites. Frustrated by the slow progress in

civil rights at home, he increasingly looked abroad, espousing the

cause of Pan-Africanism, for which he won the NAACP's highest

honor, the Spingarn award, in 1920. But in 1934 he resigned from

the NAACP to protest their goal of accommodation with white

society. Increasingly disillusioned with life in the United

States, he visited Europe and the Soviet Union, where he was

awarded the Lenin Peace Prize in 1959. In 1961 he announced that

he had joined the Communist Party and emigrated to Accra, Ghana,

at age 93. He died there two years later.

Mary McLeoad Bethune Mary McLeoad Bethune

1875-1955

One of the most widely known African American women of the

twentieth century, Mary McLeod Bethune was an educator, political

advisor, and civil rights leader. After graduation from the Scotia

Seminary in 1895, she taught at the Haines Institute in Augusta,

Georgia, then at Kendall Institute in Sumter, South Carolina,

where she met and later married Albertus Bethune. In October 1904,

Bethune founded the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for

Negro Girls in a small rented cabin, and continued to develop the

school over the next two decades. When white hospitals denied

service to black patients and training for black residents and

nurses, Bethune founded McLeod Hospital to serve the community and

to provide training for black physicians and nurses. By 1922, the

school had over 300 students and a staff of 25, later becoming the

Bethune-Cookman College. As well as working for education, Bethune

founded the Circle of Negro War Relief in New York City during

World War I, was vice president of the Commission on Interracial

Cooperation, and served as president for two terms in the National

Association of Colored Women, advising the Coolidge and Hoover

administrations on African American issues. In 1935, Bethune

founded the National Council of Negro Women and served as

president until 1949. She retired from public life on her

seventy-fifth birthday in 1950, settling in her home on the campus

of Bethune-Cookman College, and over the next five years received

12 honorary degrees.

Jessie Fauset

1882-1961

Jessie Fauset, essayist, editor, and novelist, displayed in her

work the complexities of life for literary artists during the

Harlem Renaissance and the Great Depression. Her career as a

teacher provided the stability of income and permanence that

allowed her to write her novels and essays.

As a college student at Cornell University, Fauset had started

corresponding with W.E.B. Du Bois, editor of the NAACP's journal The

Crisis, and later submitted articles to the journal. After

completing her master's degree in French in 1920, she was invited

to become The Crisis's literary editor, holding the job

until 1923 and afterward becoming the managing editor. As both a

foster mother to and a product of the Harlem Renaissance, Fauset

wrote more novels than any other black writer from 1924 to 1933.

The black characters in her novels reflect the "Talented

Tenth" and her own experiences with the hard-working,

self-respecting black middle class. Fauset left The Crisis

in 1927 to achieve a more ordered life as a French teacher at De

Witt Clinton High School. She continued to teach in New York until

1944 and later taught as a visiting professor in the English

Department at Hampton Institute.

Zora

Neale Hurston Zora

Neale Hurston

1891-1960

Born in the small all-black town of Eatonville, Florida, Zora

Neale Hurston was to become, for 30 years, the most prolific

African American female author in the United States. Despite this,

Hurston and her work drifted into obscurity until her rediscovery

in the 1970s. Much of this neglect can be attributed to the

controversy that always seemed to surround this independent and

free-spirited woman.

Protected from racial prejudice as a child and inspired by her

mother, Hurston grew into an outspoken, eccentric, and racially

proud woman, one who chose to write about the positive side of

black Americans. After moving to Washington, D.C., she attended

Howard University and first published her writing in 1921. Hurston

moved to New York City in 1925 and became one of the members of

the Harlem Renaissance. After attending Barnard College on a

scholarship and completing her undergraduate work in 1927, she

returned to Florida to collect black folklore and was awarded a

Julius Rosenward Fellowship in 1934 for her collection of

folklore. During the 1930s, her novels Jonah's Gourd Vine

and Their Eyes Were Watching God were published. Her career

produced seven books and more than fifty shorter works from

autobiography to folklore to music and mythology. After World War

II, her fortunes declined until her death in 1960, a penniless

inmate at the Saint Lucie County Welfare Home. Although she was

believed married three times, she died alone, and her grave

remained unmarked until novelist Alice Walker located it in an

overgrown Florida cemetery.

E. Franklin Frazier

1894-1962

Sociologist and educator, E. Franklin Frazier was born in

Baltimore, Maryland. In 1916 he graduated cum laude from Howard

University with a B.A. degree and accepted a position as

mathematics instructor at Tuskegee Institute. He received his M.A.

degree from Clark University in 1920 and his Ph.D. from the

University of Chicago in 1931. A grant from the American

Scandinavian Foundation enabled him to go to Denmark to study

"folk" schools. From 1922 to 1924, Frazier taught

sociology and African studies at Morehouse College in Atlanta,

then served as director of the Atlanta School of Social Work until

1927. He was on the faculty at Fisk University from 1931 until

1934, after which he became head of Howard University's department

of sociology, a post he held until named professor emeritus in

1959. Frazier was a prolific writer; he was the author of several

books including the controversial Black Bourgeoise. His

numerous awards included a 1940 Guggenheim Fellowship and the John

Anisfield Award.

James Langston Hughes James Langston Hughes

1902-1967

One of the original writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston

Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri. In 1921 he began studies at

Columbia University but left after a year, going off to work on a

freighter and traveling that way to Africa, then living in Paris

and Rome. Returning to the U.S., he graduated from Lincoln

University in 1926, publishing his first book of poetry, The

Weary Blues, that same year. Also in 1926, Hughes published a

critical essay, "The Negro Artist and the Racial

Mountain," which became a defining piece for the Harlem

Renaissance movement. During the next four decades he continued to

write in a number of forms--novels, poetry, short stories, plays,

autobiography, and nonfiction. In 1942 he began a column in a

Chicago newspaper that introduced his character,

"Simple," an African American Everyman who wittily

comments on the ironies besetting black people's lives. He

eventually published five volumes of his "Simple

Stories." Amazingly prolific, admirably versatile, and a man

capable of hearty humor as well as bitter criticism, he fell in

and out of favor with the public, but the best of his work

promises to survive.

Charles Drew

1904-1950

The man who discovered the modern processes for preserving

blood for transfusions, Charles Drew grew up in a solid but poor

family in a Washington, D.C. ghetto. His intelligence and athletic

skill won him a scholarship to Amherst College, where he was

captain of the track team, starting halfback on the football team,

and an honors student. For two years following graduation, Drew

taught and coached at Morgan College in Baltimore, earning money

to attend the medical school at McGill University in Montreal.

There he became increasingly interested in the general field of

medical research and in the specific problems of blood

transfusion. After graduation from McGill in 1932, Drew did his

three-year residency at Montreal General Hospital before joining

the faculty of Howard University, where he was eventually

appointed head of surgery.

During the last decade of his life, Drew continued his

pioneering research into the separation and preservation of blood.

When the U.S. entered World War II, he was appointed head of the

National Blood Bank program. Furious at the official government

policy that mandated whites' and African Americans' blood would be

given only to members of their respective races, he resigned from

his post and returned to Howard. In 1944 he became chief of

surgery at Freedmen's Hospital in Washington, D.C., where his

presence encouraged other young African Americans to enter the

field of medicine. Drew died in a car crash in 1950.

Margaret Walker

Born 1915

Poet, novelist, and teacher Margaret Walker spent a culturally

rich southern childhood that influenced her poetic and artistic

vision. Her father, a scholar and lover of literature, instilled

in his daughter a love of American and English classics, the

Bible, and poetry. Her mother played music, especially ragtime,

and read poetry. The family household included her maternal

grandmother, who told the children folktales. One story stayed in

Walker's consciousness and became a part of her famous novel, Jubilee.

The Depression served as the context for the 1934 publication

of her first poem, and the beginning of her association with the

WPA Writer's Project, where her experience was enriched by her

contact with other writers and artists. In 1939, Walker finished

her first novel, Goose Island, which was never published. A

collection of poetry was published by Yale University Press in

1941, also winning the Yale Younger Poet's Award. The same year,

Walker began teaching, and her long career took her to Livingstone

College, West Virginia State College, and Jackson State

University. Since her retirement from teaching, Walker has

continued to write and has undertaken rigorous speaking tours.

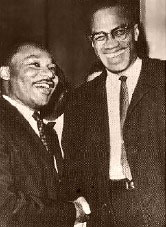

Malcolm X

1925-1965

One of the most controversial figures in the civil rights

movement, Malcolm X's career was cut short by an assassin. Born

Malcolm Little, his minister father died when he was 6. After a

childhood spent in institutions and foster homes, Malcolm headed

east, settling in Boston and supporting himself with odd jobs and

pimping. In 1943 he moved to New York where he began to lead an

increasingly marginal life. After receiving a 10-year sentence for

burglary in 1946, he was transformed in prison, becoming a

follower of Elijah Muhammad's Nation of Islam movement. Paroled in

1952, he was ordained as a minister, taking the name Malcolm X.

His militant stance and depiction of whites as "blue-eyed

devils" won him considerable press coverage and a good deal

of suspicion from the white community; in many ways he seemed the

antithesis of Martin Luthor King, Jr., who preached non-violence.

In 1963 he formed the Organization of Afro-American Unity, and in

1964 he made a pilgrimage to Mecca and converted to orthodox

Islam.

At

the time of his death, Malcolm X seemed to be moderating his

hostile view of whites. Nonetheless, he spoke in the months before

his death of his fear that he might be assassinated by opponents

in the Nation of Islam or by the U.S. government. His assassin was

apparantly a member of a dissident black group, though mystery

still remains about the event. At

the time of his death, Malcolm X seemed to be moderating his

hostile view of whites. Nonetheless, he spoke in the months before

his death of his fear that he might be assassinated by opponents

in the Nation of Islam or by the U.S. government. His assassin was

apparantly a member of a dissident black group, though mystery

still remains about the event.

Download a sound file from an early Malcolm X speech.

Running time :10

128K .aiff format

Martin Luther King, Jr.

1929-1968

The most influential leader in modern civil rights, Martin

Luther King, Jr. was born in Atlanta, Georgia. His father was a

Baptist minister, providing a strong religious tradition for King.

He attended the Atlanta public schools and was graduated with his

A.B. from Morehouse College in 1948 when he was 19 years old. He

went on to Crozer Theological Seminary and graduated in 1951 at

the top of his class, going from there to Boston University for

his Ph.D. There he met and married Coretta Scott in 1953. By then

an ordained minister, King took the pastorate of the Dexter Avenue

Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, and quickly became involved

in the civil rights movement. He soon found himself in the

forefront of a boycott of Montgomery's segregated buses, which led

to a Supreme Court decision in 1956 against Alabama's segregation

laws. Following this triumph King was made president of the newly

formed Southern Christian Leadership Conference, committing his

life to nonviolent activism and bringing the civil rights movement

to the forefront of American public life.

Between 1960 and 1965, King continued to lead numerous

demonstrations and protests on behalf of civil rights, leading the

1963 March on Washington where he delivered his most quoted

speech, "I have a dream. . . ." In 1964 he was awarded

the Nobel Peace Prize. Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot and killed

on April 3, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee; he was there to support

striking sanitation workers. His death devastated the nation.

Download a sound file from King's "I Have a

Dream" speech. Running time 1:03

689K .aiff

format

Lorraine Hansberry

1930-1965

Lorraine Hansberry's life as celebrated playwright and activist

artist earned her the tile of "Warrior Intellectual."

When she died at age 34, her testimonial was demonstrated by the

number of eulogies given by prominent figures in government, the

arts, and the civil rights movement.

Born into an affluent family in Chicago, Hansberry grew up

among such family friends as Paul Robeson, Duke Ellington, and

Jesse Owens. Her interest in theater was sparked during her years

at the University of Wisconsin, but in 1950 she left college for

New York and "an education of a different sort." She

worked as a writer for Freedom, Paul Robeson's radical

black newspaper, and covered such issues as colonial freedom,

equal rights for blacks, the conditions of Harlem schools, and

variants of racial discrimination. She married Robert Nemiroff, a

white student whom she met on a picket line at New York

University, where he was a student.

Lorraine Hansberry left Freedom in 1953 to concentrate on her

play writing. earning her position in American letters with the

production of A Raisin in the Sun in 1959, becoming the

first black woman to have a play on Broadway and the first African

American to win the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. Her

success revitalized black theater, enabling other blacks to get

their plays produced. Politically active throughout her short

life, Hansberry worked to abolish the House Un-American Activities

Committee, served on a panel to meet with Attorney General Robert

Kennedy about the racial crisis, and was instrumental in civil

rights.

Colin Powell

Born 1937

Born and raised in New York City, Colin Powell would go on to

become one of the country's best known figures during Operation

Desert Storm, the U.S.-led United Nations offensive against Saddam

Hussein's Iraq in 1990-1991. Upon graduation from City University

of New York in 1958, Powell received a second lieutenant's

commission and became a career army officer, serving with

distinction in Vietnam. Rising through the ranks and increasingly

responsible commands, from 1987 to 1989 he was a presidential

assistant for national security in the Reagan administration. As

such, he was the highest ranking African American in the

administration. In 1988 he was nominated to become one of only ten

four-star army generals. His responsibilities included the command

of all army personnel serving in the mainland United States and

the defense of the mainland in the event of enemy attack. During

the Reagan years he advised the president at summit conferences in

both Moscow and Washington, D.C. In 1989 he became the first

African American to serve as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of

Staff, a position he held until he retired from the army in 1993.

Upon retirement he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Charlayne Hunter-Gault

Born 1942

Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Hamilton Holmes were the first two

black American Students to attend the University of Georgia in

January 1961. Students rioted to protest. Hunter-Gault says of the

experience, "If you've ever been in the middle of a riot or

the eye of a hurricane, you know it's very calm. That is exactly

how I felt the night of the riot." Hunter-Gault knew at the

age of twelve that she wanted to be a journalist, and despite the

oppressive racial climate she encountered at the University of

Georgia, she stayed and earned her B.A. in journalism in 1963.

After graduating from college, Hunter-Gault went to work for

the New Yorker magazine, and in 1967 she received a Russell

Sage Fellowship to study social science at Washington University.

Later she went to Washington, D.C., to cover the Poor People's

Campaign, and in 1968 she accepted a position with the New York

Times. Over the years Hunter-Gault has received numerous

awards, including the New York Times Publishers Award, two

National News and Documentary Emmys, and the George Foster Peabody

Award, given to her by the University of Georgia for the

documentary "Apartheid's People." Presently she is a

journalist on PBS television.

August Wilson

Born 1945

Despite never finishing high school, August Wilson holds the

distinction of having twice won the Pulitzer Prize, for plays

depicting the African American experience: Fences and The

Piano Lesson. Wilson set out to create a cycle of plays on the

African American experience, concentrating on the twentieth

century. His first play, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, set in

the 1920s, won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award, and his

Joe Turner's Come and Gone, set in 1911 and focusing on black

migration to the North, was voted the best new play in 1988 by the

New York Drama Critics Circle. While many of his plays have opened

in New Haven, Connecticut, all have moved on to long New York runs

and to countless productions elsewhere. Wilson is also founder of

the Black Horizons Theater Company.

Carole Moseley-Braun

Born 1947

In 1992 Moseley-Braun was elected a Senator (D.) from Illinois,

becoming the first African American woman to sit in the U.S.

Senate and only the second African American since Reconstruction

to be a Senator. The daughter of a Chicago police officer,

Moseley-Braun received a law degree from the University of Chicago

and worked in the U.S. Attorney's Office, where she won the

Special Achievement Award. In 1978 she was elected to the Illinois

House of Representatives, where she was voted Best Legislator each

of the ten years she served. In 1988 she became the first African

American to hold high office in Cook County when she was elected

Cook County Recorder of Deeds, an important stepping stone to her

Senate race.

Cynthia A. McKinney

Born 1955

One of the strongest voices for modern black

interests in the Georgia's state legislature has long been J. E.

"Billy" McKinney, a civil rights activist who first

served in 1973. Fifteen years later his daughter, Cynthia, a

political scientist who had taught at Clark Atlanta University and

Agnes Scott College, a century-old woman's college in DeKalb

County, also won a seat in the state House. Together they became

the only father-daughter legislative team in the country. Cynthia

McKinney brought to her post the same commitment to defending

minority interests her father had; she was just 10 when the Voting

Rights Act was passed and she has recalled that, as a child, she

often rode on her father's shoulders as he walked in civil rights

marches. She won a seat on the Georgia legislature's redistricting

committee and helped to craft the two new black-majority

districts. In 1992 McKinney ran as a Democrat for the right to

represent one of the districts she had helped create, the

Eleventh. She won with 73% of the vote and was later reelected to

a second term.

Selected Bibliography:

Barone, Michael & Ujifusa,

Grant. The Almanac of American Politics 1996. Washington,

DC: National Journal Inc., 1995.

Low, W. Augustus. Encyclopedia

of Black America. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Salem, Dorothy C. African-American

Women: A Biographical Dictionary. New York & London:

Garland Publishing, 1993.

Smith, Jessie Carney, ed. Notable

Black American Women. Detroit, MI: Gale Research Inc., 1992.

Smith, Sande, ed. Who's Who in

African-American History. Greenwich, CT: Brompton Books Corp.,

1994.

|